The July sun had dipped below the horizon as Darnell Rice stepped off the express bus and edged toward Big Dam Bridge, standing 90 feet above the waters of the Arkansas River. The bridge, built for pedestrian and bicycle traffic, is the longest of its kind in North America, but Rice had no intention of walking almost a mile to the other side.

He was about to jump.

His dream of being the first male in his family to graduate with an advanced management degree from Webster University was cut short by his mother's debilitating bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Surviving on $9.25 an hour as a rental sales associate at Avis with no vehicle of his own, Rice was battling homelessness and overwhelmed with child support bills he couldn't afford.

A product of childhood rape, Rice's early years were marred by trauma left untreated. The 39-year-old Missourian knew of the enormous stigma attached to therapy or even speaking to friends about his deteriorating mental health.

Jumping off that bridge would have reduced Rice to a statistic all too familiar among men in the United States, who are four times as likely as women to take their own lives.

Across the Atlantic, Abe Ball, 17, had given up too.

Amazon Prime had just delivered a six-pack of Van Der Hagen stainless steel razor blades to his mother's leafy front porch in an upscale London suburb.

He began unpacking its contents, convinced that dying would be the only thing in his life he could control after a miserable past 12 months that had seen him be treated for melanoma, drift further away from his divorced parents, twice be on round-the-clock suicide watch in a youth psychiatric ward, and lose contact with his friends.

But, like Rice, a razor blade ended up saving him.

Three years on, Rice and Ball attribute their recovery not to a doctor or therapist, but to a socio-cultural institution that has

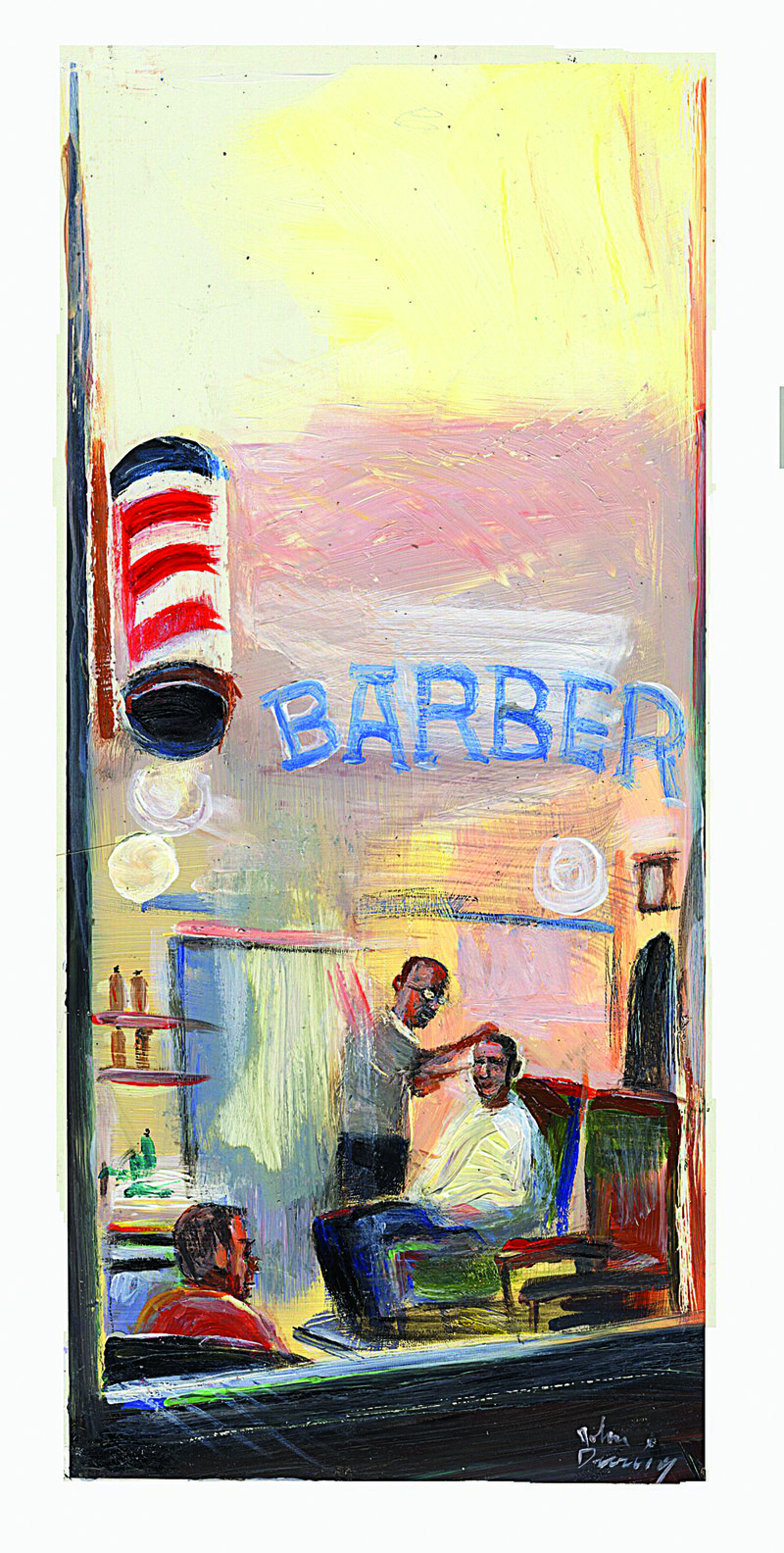

served as a social hub for communities across the globe: the barbershop. More recently, this institution--a place where you participate in mundane conversation as you get a monthly trim--has been identified as a powerful weapon against depression and mental health disorders, the leading causes of suicide worldwide.

"I love the fact that, as a barber, I can make someone's day better because too many men suffer in silence," said Ball, who is training to become a barber in London.

Barbers across the globe are seizing opportunities to engage in intimate, inexpensive and extended one-on-one conversations with strangers who appear to be suffering in silence but are comfortable enough to confide in their dependable barber.

With self-inflicting deaths occurring roughly every 15 minutes, some barbers are identifying themselves as mental health advocates and first responders for vulnerable men who sit in their chairs.

Dozens of interviews with barbers, clients and psychologists are shedding light on the potentially life-saving role barbers can play by reaching those who might otherwise shun professional help. Their unique position in society means they are not masquerading as doctors or counselors, but are bridging the gap between vulnerable members of the community and already-established mental health resources and services.

There are too few mental health providers to meet the needs of the U.S. and globally, said Ali Mattu, a clinical psychologist at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, adding that the universality of the barbershop could be crucial in tackling the worldwide depression epidemic, which the World Health Organization predicts will be the largest contributor to disease burden by 2030.

"If we can help barbers learn more about mental health, we can reach a much larger population that we could not reach otherwise," Mattu said. "The barbershop is a possible avenue because it is a culturally sanctioned way to take care of yourself in an environment where there is trust and frequency of contact."

Mattu, host of YouTube channel The Psych Show which seeks to demystify mental health to its 38,000 subscribers, said that there are visual ways in which barbers might be the first to spot signs of trouble as well. With over 200,000 cases annually in the U.S., trichotillomania occurs when somebody has a compulsion to pull their hair out from their head, arms, or eyelashes, oftentimes as a result of overwhelming emotional stress and anxiety.

"Barbers could be the first to notice this, or they might be instrumental in helping someone overcome this," said Mattu. "A barber who knows enough about this condition could go a long way to help them overcome this shame."

Use of barbershops to raise awareness of depression as a public health crisis is part of a trend toward arming professionals who regularly interact with the public with better training in mental health counseling.

Since opening last May, Chicago-based Sip of Hope became the first cafe in the world to divert 100 percent of its revenue to funding suicide prevention programs. Its baristas and volunteer staff are given mental health first-aid training in order to strike up possibly lifesaving conversations with some of its patrons. This past year, librarians in Sacramento and Philadelphia have also received mental health counseling to identify and support homeless people seeking shelter in their libraries.

In African American communities, a growing number of organizations are leveraging the cultural significance of the barbershop as a pillar of community life and to provide other basic health and educational services. In Harlem, Barbershop Books, a non-profit literacy organization, has partnered with locations across New York to create child-friendly reading spaces in barbershops and offer training to barbers to combat high rates of cross-generational illiteracy.

Dozens of barbershops in Los Angeles are measuring blood pressure to help spot signs of heart disease, a leading cause of death among men in the U.S. In his 2016 TED talk in Vancouver, Joseph Ravenell, associate professor of population health and medicine at New York University, spoke about how he saw the barbershop as an ideal solution for a demographic with a unique problem. He founded the Mister B Initiative, which turns barbershops into temporary clinics where medical students show barbers how to measure blood pressure and teach them to initiate productive discussions about leading a healthier lifestyle.

"Barbering within the African American culture has been elevated to a special type of skilled labor," said Maureen Elgersman Lee, associate professor of history at Hampton University and executive director of the Black History Museum and Cultural Center in Jackson Ward, Va. "Black barbershops remain highly gendered, socially intimate spaces that offer fraternity, wisdom and respite from the multiple external spaces that black men must move through beyond those doorsteps."

LeBron James' hit HBO show The Shop may have sparked an interest in the barbershop as a forum for free-ranging discussion among males, but the historical and cultural significance of the barber's chair as a space where everything from the mundane to the profound is discussed dates back centuries.

Barbering is one of the oldest professions in the world, tracing back to ancient Greece. Its practitioners have served many purposes beyond cutting hair. Throughout the Middle Ages, barber-surgeons extracted teeth and performed minor surgeries. The red and white poles often affixed to barbershops are linked to the medieval medical procedure of bloodletting; the red and white stripes denote the blood and bandages used to stem the bleeding.

Lorenzo Lewis was hoping to create some history of his own when he founded a non-profit organization called The Confess Project in 2016. The motivational speaker's barbershop initiative started in Little Rock, which has earned a reputation for being an epicenter of historic change in the civil rights era with racial desegregation.

His mission is to leverage the historical and cultural significance of the barbershop as one of the last bastions of unregulated speech in African American communities across the South and Midwest to encourage discourse about mental wellness and depression.

"The South is home, and we need to take care of the men there first," Lewis said. "Men have not socially, historically or systematically been able to have a safe space to discuss their mental health, but the barbershop is our robust model that lets men--black men especially--see themselves in the best way."

One of the first people Lewis' program saved was Darnell Rice.

"I was about to just give up on life and give up on myself," Rice said, recalling that night three years ago on the bridge in Little Rock. But he gave life one more chance. His mental health battles persisted, but his life changed when he met Lewis at a barbecue at his local neighborhood park by Tall Timber Boulevard a few months after. "He was manning the grill most of the time," Rice said. "But we eventually had a conversation about my struggles and he invited to take me onboard The Confess Project."

Lewis has since traveled to Kentucky, Tennessee, South Carolina, Atlanta and New Orleans to teach his flagship program, Beyond the Shop, designed to facilitate an interactive 60-minute discussion around mental health among African American men and boys in the barbershop. Lewis, or a member of his team from the Project, initiate group discussions in these barbershops as a way of bridging public health disparities with marginalized males in need of treatment for mental health-related issues.

For Lewis, men of color--like Rice, now a program facilitator at The Confess Project--are avoiding professional help because of "racial micro-aggressions" in America caused by the dearth of black representation in the medical community, not to mention financial barriers.

A long-term sufferer of depression himself, Lewis was born in a prison and spent his formative years volunteering in his aunt's beauty salon in Little Rock, where he met barber Sylvester Stewart, who came to be his mentor.

In January 2018, J. "Divine" Alexander, who had been struggling with depression for over a decade, hosted the Confess Project's Beyond the Shop program at his Campus Barber Shop in Louisville, Ky. "There needs to be a constant conversation around mental health issues that concern young men and boys because too many of them are going undiagnosed for fear of looking weak," said Alexander.

This past January, a member of his community, Tami Bridges, lost her 10-year-old son, Seven Bridges, to suicide after he had been aggressively bullied for wearing a colostomy bag due to a birth defect.

"Somebody as young as 10 was facing issues that we as a society have not yet discussed broadly and widely," said Alexander, his voice heavy with resignation. Seven's death marked the eighth youth suicide this academic year across the school system in Louisville, according to Renee Murphy, a spokeswoman for the Jefferson County Public Schools district.

Suicide and depression had been on Jordan Jones' mind long before he met Lewis in an Instagram-coordinated meetup last year in Atlanta and agreed to become Michigan's ambassador for the Confess Project. As a teen, the now 23-year-old from Pontiac, Mich., remembered March 18, 2012, all too vividly.

He was walking home from an outdoor basketball session when a member of his church told him to rush. Three police cars surrounded the home with their blue and red LED lights flashing. At first, he thought the commotion was for his elderly neighbors who were accident-prone until he was told that his father had committed suicide after another rowdy argument with his mother.

"I was in shock and have been struggling to let it go since," said Jones. "I thought the void could be filled if I dedicated all my time to things like debating and basketball, but I hit rock bottom as I went into senior year."

Writing hip-hop music was a good coping mechanism for him, but he said he only really started healing after his many sessions with Keiana Walton, a medically-trained Confess Project ambassador from Washington, D.C.

"Mental health does not have a color, but I like the idea of starting with African American men because we really do not have a strong support system," Jones says. "All we have are our barbers."

Jonathan Harounoff is a British graduate of Columbia Journalism School. He is also an alumnus of the Universities of Cambridge and Harvard where he studied Arabic, Middle Eastern history and international relations. He currently works as an analyst and is based in New Haven, Conn.

Editorial on 09/08/2019